Mr. Annas, on March 21, 1960, the South African apartheid regime killed 69 demonstrators protesting against racial segregation in the township of Sharpeville. After that, the situation in the country became increasingly unbearable, more and more jazz and other musicians went into exile. How did this exodus change South Africa’s jazz scene?

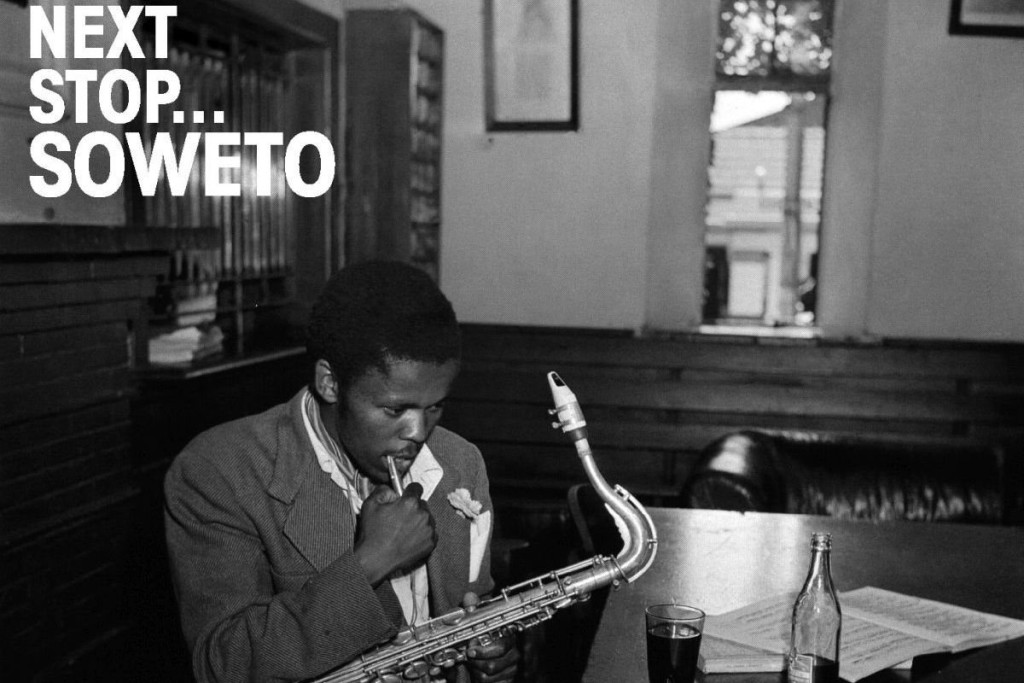

Sharpeville was a turning point. The ruling National Party demonstrated that it was determined to defend and enforce apartheid policies to the utmost. A first wave of successful musicians like Abdullah Ibrahim, Miriam Makeba, Kippie Moeketsi and Hugh Masekela left the country; over the years others increasingly followed them. Younger people who played a recognizably more contemporary jazz initially filled in the gaps they left behind. But the regime slowed down developments. Between 1960 and 1970, fewer than twenty local jazz albums were issued – in a country with a well-functioning music industry.

What significance did jazz have back then for the broader population of South Africa?

In the townships where the non-white majority of the population lived, jazz was one of the most popular music genres. Along side it Kwela and Mbaqanga were the major styles of pop music. Both were rooted to varying degrees in jazz and related sounds. Kwela had a more swing-oriented beat, but Mbaqanga was – roughly speaking – more African, referring to models from Zulu culture.

What was the fundamental stance of the apartheid regime to music styles like Kwela, Mbaqanga and jazz?

Music was generally not prohibited. Although airtime was strictly regulated, there was jazz on the radio. But jazz was the kind of music that appeared most suspicious to the regime. According to sociologist David Coplan, the ruling classes regarded jazz as “the devil’s own soundtrack.” With its locally focused broadcasters, the government propagated ethnically pure pop music but not only between Blacks and whites, also among the various Black population groups.

But this segregation didn’t apply to jazz?

In South Africa, jazz was the music genre in which Black, white and colored people performed onstage together. That’s why the regime was very suspicious of jazz. Additionally, white musicians had freedoms that their Black colleagues did not: They were more independent in their material, better protected from persecution, and had easier access to the means of production. Yet the creativity was mostly Black. The ethnic composition naturally posed problems. For example, The Blue Notes, a band that were categorized by the regime as “mixed,” could not easily perform in so-called “Black areas,” or in those of the whites. This led to the curious situation that the white band member Chris McGregor often performed as “colored” in order to be able to play with the Black musicians.

So jazz was political music in South Africa?

Everything about jazz was highly political. It was charged by the struggles of the communities in the United States and their quest to link jazz with liberation. The South African government’s tolerance ended finally with the establishment of the term “free jazz,” and not merely with the aesthetic radicalization of this music on the other side of the Atlantic. Max Roach’s album We Insist! – Freedom Now Suite of 1960 linked liberation in the United States with that in South Africa. That was obvious to the censors, of course.

To what extent did outside influences such as this effect music in South Africa?

Since the 1930s, South Africans used swing and then, gradually, bebop as patterns to develop their own sounds and codes. Records always came in through the seaports, but also by mail. That was monitored, however, and when people picked up their records they would sometimes find individual tracks had been scratched by the censors. Other styles that became important in South Africa in the 1980s, such as house and hip-hop, also came from the US.

What was jazz doing in the 1980s?

It was pretty well finished by then. Its protagonists were exiled, dead, worn down or became more focused on their small, local audiences. The band Juluka, in which the white Johnny Clegg and the Black Sipho Mchunu invented a new kind of collaboration against apartheid, was symbolically important, however. Clegg’s self-portrayal as the “White Zulu” was a powerful mockery of official racial politics.

What role did music play in the collapse of apartheid in 1994?

The end of apartheid was a process that music could only accompany. The shifts in world politics, the country’s almost total insolvency, the erosion caused by the boycotts on the arts and, most importantly, sports, had shredded apartheid’s strategy. And we mustn’t forget that civil and military resistance had driven the regime to employ ever more brutal methods of terror – and ever further into international isolation.

After the end of apartheid, Kwaito, a variation on house rapped in local languages, experienced a veritable boom. Moving from little to nothing before that, its lyrics became openly political. What significance did this music have for the burgeoning identity of the country, which from then on aimed to be a “Rainbow Nation”?

Kwaito, largely lifeless today, was hugely important to music culture at that time, because in it a non-white style could express itself verbally for the first time in history. Arthur Mafokate’s song “Kaffir” (the K-word corresponds to the American N-word) in particular marked a radical transition from the symbolic, to articulate lyrics. This is why jazz was so popular at particular times: because as music without words it used different codes than lyrically based genres. Often these were codes that were not understood in the white mainstream.

How is jazz doing in South Africa today?

The genuinely South African style of jazz with its own local history has been experiencing a renaissance for several years now. In particular, the young people who had a formal education are turning to the jazz genre and its history now, and its potential for resistance is being recomposed for the present time. At present, it’s neither socially relevant nor a strong economic factor, but even so, it’s a new beginning of local jazz emanating from the most important historical moments.