Erich Hörl: What do you think is the problem that the concept of the technosphere is reacting to or answering to?

Peter K. Haff: The technosphere is my way of constructing a concept to try to understand and analyze the sum of humans and their technology, essentially all of its ramifications and all of its parts, on a scientific basis. It would include individuals, it would include these bottles of water on the table, it would include the internet, it would include art museums and the art within the art museums. Basically, we are talking about civilization when you sum up all of these endeavors and impacts. The approach is, if you have a system that you can define well enough, then there is a procedure for dealing with that, which we often take in science, and that is to try to derive some physically-based rules or principles that would apply to it.

When would you date this, the emergence of something like a technosphere? What is the difference to other spheres such as the atmosphere or the biosphere?

It is a convenient choice: historically, geology has deconstructed, shall we say, the world, into spheres. At least for the surface part of the world. You have for example the atmosphere, and the “sphere” part just means that it surrounds. So if we go to the other side of Berlin we will find that the atmosphere is still there. And then the hydrosphere is another sphere, the water is fairly widely distributed. And these are also dynamic spheres; like the technosphere they consume energy, they’re highly organized; they have parts that interact with one another, just as the parts of the technosphere do. I’m interacting with you and interacting with the audience; and the molecules and the water are interacting with their neighbors, and so on.

So, I think it was my geological background that led me to calling it a sphere. The other point that your question raises is that, since this is the Anthropocene Project, why not call it the Anthroposphere? The reason for not calling it the Anthroposphere is because of a term in your writing which I found to powerfully underline my own impression of what is going on in the Anthropocene, the point I am trying to make through analysis of the technosphere, namely, the Anthropocene illusion [„anthropozäne Illusion“] in the German original). My interpretation of the Anthropocene illusion was the tendency for humans to put themselves at the center of things; so when we think of the climate problems and other environmental problems, we usually think of these as due to human impact. Of course, at some level, they are due to human impact, but there are many other things going on in the world that embed humans in such a way such that humans are not really acting completely independently and as free agents in doing these things, but there are much larger forces let loose in the world. These are the forces of the technosphere.

I am glad that you didn’t call it the Anthroposphere. That doesn’t mean that we have to cross out the position of the human, on the contrary, but to reformulate it. And in your concept that is exactly what is happening, because you say the humans are part of technology; and the constitutive part of this Anthropocene illusion was first of all the kind of concentration of all agency on the human. It was exactly this concentration that led to an explosion of agency, of non-human agency to be precise. What is happening today is that we are witnessing the disenchantment of the Anthropocene illusion because of the distributed agencies we start to witness more and more exactly because of and as a consequence of technologization. This makes necessary a reformulation of the place of the human and it is exactly this reconsideration that happens when thinking the technosphere.

So the question was whether one could see some other relations or possible end-points where you could learn something about the construction of the modern world that was independent of human agency per se.

You think, then, that the technosphere would be a notion for a profound rearrangement of humans and non-humans. Technical entities of course are non-humans. What does it mean to inhabit, or how to say it, what does it mean to dwell in the technosphere?

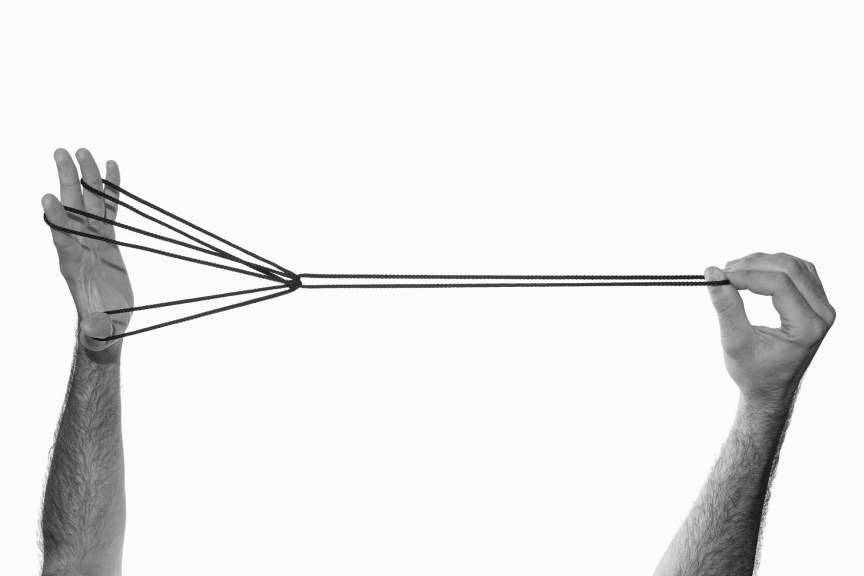

Let me put it this way: the technosphere depends implicitly and completely on human functionality, but we are in its grip, and we are being pulled along by it, we cannot escape.

Let’s come to your accentuation of the autonomy of technology as condensation as well as expression of an ongoing decentering of the human. Already the Nazi project, for example has essentially to do with this question; technology seems to get a certain autonomy and at that time the big issue was that of governmentality and master technology. To a certain degree this nazistic fascination with control that in the end penetrated all modes of existence and all levels grew out of a discussion about the autonomy of technology we had in the 1920s with Jünger, Heidegger and others. In the 1950s in Germany, this issue came up again and this time it was the big displacement or decentralization of the human that was the scandal. Fifty years later, the interesting point for me is, that the same formulation came up in your work: the autonomy of technology. But now, it’s nothing scary, it’s something that forces us to shift our perspective, to change our ways of thought, our strategies, our conceptual and theoretical strategies, and that, for me, is one of the most important points. The becoming autonomous of technology is not anymore (like it was from the 1920s to the 1950s) a problem of mastery, will and nihilism, but it compels us to a revolution in thought, even a revolution in our theoretical attitude [theoretische Einstellung], to follow Husserl. And the whole problem of thinking the technosphere has to do with and is maybe one of the starting points of this deep reformulation of our attitude that will be – as I argue elsewhere – a technoecological attitude. Could you develop a bit your notion of autonomy?

Autonomy is key, and reflects the necessities of a system too large for human understanding, but that must yet survive. Many people think that we control technology; locally we do, but no, we are actually like a molecule in a wave, we are moved along by the wave. Locally humans may have authority, of course, but at the large scale the system runs itself, without primary regard for human concerns. It’s trying to survive; it’s doing whatever is in its own best interests.