It was midnight, July 25, 1966, misty and very humid. A ship had unloaded its cargo at Shahpour port in the Persian Gulf and was heading homeland for Greece. Drifting off course, the ship became stranded just off the coast from Baghoo, the village on the island of Kish – so close to shore, in fact, that it could easily have run aground on the island. One of the villagers once told me that for seven nights the ship’s lights lit up the coastline and nearby village, which in those days didn’t have electricity. Just a boy then, he brought melons to the ship’s crew in exchange for canned fruit. On the eighth night, the ship ran out of fuel, its lights dimming and finally going out. Much work was done to tow the ship back into deeper waters but it only moved a few centimeters.

Today the ship has completely rusted over. Every time I happen to stop by, it seems as if it has been pulled a little further into the Gulf. In reality, it is the coastline that’s slowly wearing down into the sea. For forty-five years, the ship has stubbornly watched the island. Tourists come from all over Iran to view it silhouetted against the setting sun. With time, it has merged with Kish’s tropical sunset. I believe that Kish’s modernity began at midnight on July 25, 1966, when the steamship stranded off its coast. The marooned ship prophesied what would become Kish’s awry odyssey along the map of the modern world.

A Brief Introduction

For a long time Kish was a forgotten island in the Persian Gulf, left to its destiny and deprived of the riches and advancements that the northerly parts of Iran were enjoying. The islanders provided for themselves through fishing and unsteady farming – but most of all by importing illegal goods from neighboring countries across the Gulf. In the island’s first official census in 1956, the population numbered a mere 760. This was less than half of the population registered six years earlier by the geographic department of the Iranian national army. Since then, poverty had forced people to migrate to the countries on the south of the Persian Gulf. Permissive trade and customs regulations and the ease of traveling had turned the Arab sheikdoms into a true “free-trade zone,” which lured many people away from Kish and other southern parts of Iran. In 1955, when visiting Iran’s ports in the Persian Gulf, the newly appointed customs CEO also stopped at Dubai’s free-trade port. He was impressed by its many facilities. Two years later, when he was Minister of Customs, he promised to establish a free zone in Iran’s southern ports as well. However, this did not happen straight away; that is, not until the political scene in the neighboring Arab countries changed did the authorities in Iran really begin to take any notice of Kish Island.

The nationalization of the Suez Canal by Egypt in 1956 and the July 14 Revolution two years later that overthrew the pro-Western monarchy in Iraq, had heightened Pan-Arab sentiments. Radio signals from neighboring states, instigating Arab nationalism, were reaching Iran’s Arabic-speaking south, including Kish. They often criticized the Iranian government for allying with “Western imperialism” and discriminating against its Arab minorities. This alarmed the Shah and made him rethink the policies regarding the southern part of Iran. Still, only a decade later, a plan was drawn up for Kish: it was to become a “modern” and “progressive” destination for an exclusive brand of tourism. The government’s plan was to develop the island into an international tourist- and free-trade zone that would attract the wealthy elites from the oil-rich Arab sheikdoms as well as from the West. In 1968, Kish was officially designated a free-trade zone; and to cut out any competitors, all plans to turn existing trade ports into free zones were cancelled.

The first structure erected on Kish was the Shah’s palace. He had decided that the island should be an exclusive resort where he would spend the winter with his family and receive guests.

The island’s association with the royal family undoubtedly highlighted its allure and granted it geopolitical significance. It was only natural in this light that the royal family hosted its high-toned inauguration, for which a select group of international guests were flown in with a Concorde airliner. The date was October 29, 1977; the protests preceding the revolution on mainland Iran were slowly getting underway.

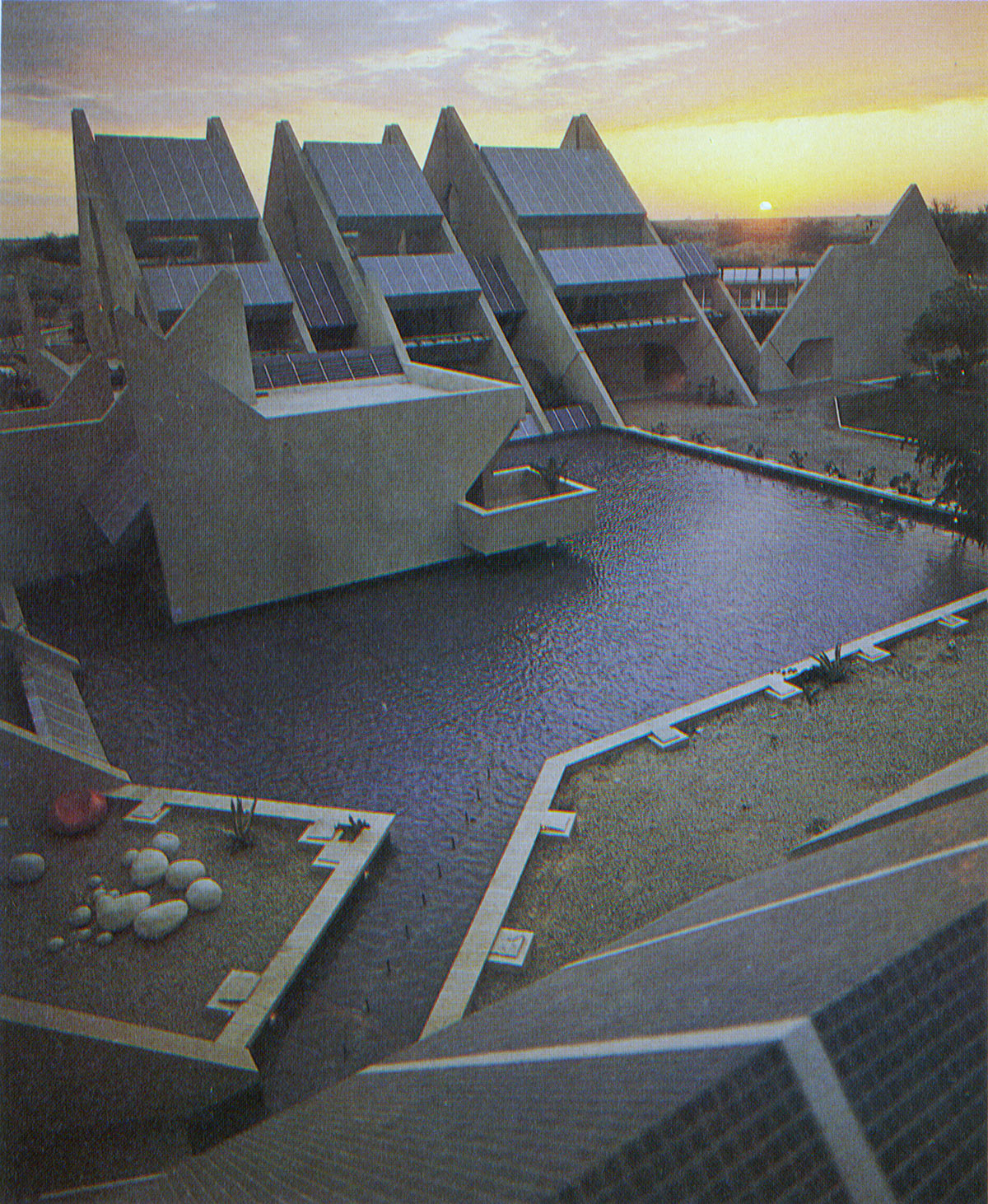

The Shah’s palace on Kish Island. Source: Iran Elements of Destiny (Toronto, Canada: mcClelland & Stewart, 1978, p. 350).

I once calculated that if I were to walk from where the Greek ship was stranded all the way to the opposite side of the island, in a straight line exactly aligned with the ship’s axis, I would end up at a curved tip on the northeastern shore, renowned for being the best place on the island from which to view the sunrise. The development of the resort began right at the foot of this shore. With its sandy beaches, it was considered the best place for leisure and entertainment. The site for the proposed resort was already inhabited, and this meant it had to be “evacuated” before the resort could be built. The spot had been the administrative heart of the island and home to its largest village, Masheh, the Farsi word for “trigger.” In 1971, a governmental entity called The Kish Development Organization (KDO) was established to manage the new developments on Kish. The budget for the KDO was provided by the Development Bank (Bank-e Omran) and the National Intelligence and Security Organization (SAVAK). KDO first built another village farther to the west, adjacent to the existing village of Saffein, and moved the 700 inhabitants of Masheh there, mostly against their will. The new village became New Saffein, and Masheh was renamed Old Saffein.

Walking through New Saffein is a truly strange experience. The architects have painstakingly tried to simulate, in both use of materials and design, the features of vernacular architecture and planning typical of southern Iran, as was found in Old Saffein. In an information booklet that accompanied the 1977 official unveiling, handed out to foreign visitors, New Saffein is described as a village displaying the “genuine traditional lifestyle” of the native inhabitants of Kish as it had been during the time of Marco Polo.