My father-in-law, Pedro Medina Sotomayor—or Don Pedro, as I call him—fills silences with stories. He’ll talk about his years as a taxi driver or union leader or the time one of the thirty-three miners stopped by his house to visit the miniature replica he built of the Chilean mine that collapsed in 2010. He has no filter when he talks, is always on time, loves to tease, and takes pride in doing a job well and on time. He also played a central role in Chile’s short-lived attempt to build an automobile for the people.

Don Pedro worked for the auto-manufacturer Citroën during the 1960s and early 1970s. When the socialist candidate Salvador Allende won the presidential election in 1970, Don Pedro was Director of Methods at Citroën Arica in northern Chile. Allende’s government, Popular Unity, pushed to increase the quantity of low-cost goods for popular consumption. Such policies paralleled those for income redistribution, increased production in the state-run sector of the economy, and decreased unemployment. From 1970 to 1973, the Allende government manufactured low-cost automobiles, motorcycles, sewing machines, household electronics, and furniture. Consumption and production thus formed important and interlocking parts of Chile’s plan for peaceful socialist change.

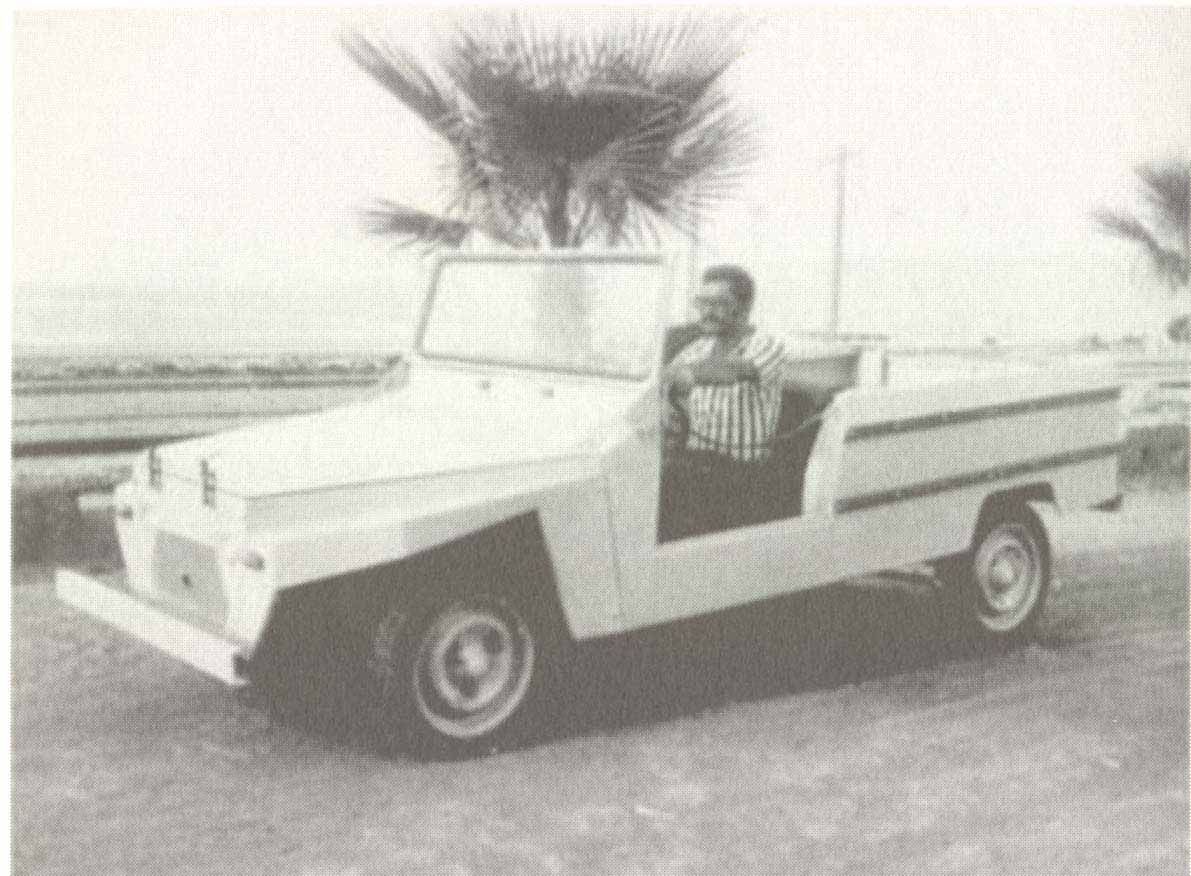

Following Allende’s election, Pedro Vuskovic, minister of economy, ordered the manufacture of a utility vehicle akin to the jeep that would cost less than 250 dollars to produce. Using funding and technology from its parent company, Citroën, the Chilean plant where Don Pedro worked drew up plans for a utility vehicle modeled after the Citroën Baby Brousse, a car the French manufacturer had designed for public transport in Vietnam. The Chilean plant also drew inspiration from the Citroën Méhari, a low-cost utility vehicle manufactured in Argentina during the 1960s. The Chileans named the new design “Yagán” in reference to an extinct indigenous people from Tierra del Fuego, Chile’s southern tip. While the chassis, motor, and suspension system for the car were repurposed from other Citroën models, workers in the Citroën Arica plant designed much of its body and tested it for manufacture.

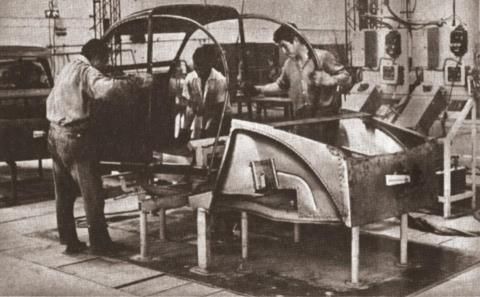

Cristián Lyon, head of Citroën during the Allende era, described building the Yagán as an artisanal undertaking rather than a science: cutting here, straightening there, and creatively combining parts from Citroën vehicles past to produce a distinctively Chilean automobile. “I insist it was almost a metaphor for the history of Chile,” Lyon remarked in an online interview, perhaps referring to the ad hoc willingness of Citroën workers to construct something new from the ground up, regardless of the hurdles involved.

On September 11, 1973, a military coup brought Chile’s socialist experiment to an end. Citroën sold the remaining Yagáns to the Chilean military. There are stories of the military’s dropping the cars from low-flying airplanes to see if they could be used to patrol the arid border between Chile and Peru. The cars did not fare well.

Chile returned to democracy in 1990. Since the late 1990s scholars and journalists have regarded the Yagán as an example of Chilean technology under socialism, and a material representation of Allende’s utopian project that never came to pass. Chilean television, film, and print media all have named the Yagán as an important milestone in Chile’s automotive history, and it was featured as an installation in Chile’s 2010 Design Biennale as representative of the event’s theme “Chile se diseña” (Chile Designs Itself). The 2003 documentary La Huella del Yagán (Tread of the Yagán, directed by Patricio Díaz and Enrique León) portrayed the car as an object of nostalgia. It filmed the journey of two young Chileans as they drove a Yagán from Santiago to the northern city of Arica, where the car was manufactured, bringing the historic vehicle back to its birthplace while recounting its origin story. The history of the Yagán thus parallels the ruptures and reconciliations of Chilean history, moving from an automobile for the people to a military transport vehicle to a way to remember, understand, and interpret the Allende period.

The iconic photograph of the Yagán shows Don Pedro sitting in the driver’s seat; in the background are the beach and palm trees of Arica—the city of “eternal spring.” The photo has brought him in contact with filmmakers, journalists, historians, and automobile aficionados. He is a celebrity in the Citroën Yagán Facebook group.

In 2004, I asked my husband, Cristian, to interview his father about the experience of working on the Yagán project, which I recorded and had transcribed. The resulting transcript is a family history as well as a history of technology. It illustrates how the ideas of the Popular Unity government were carried out on the ground and the daily acts of ingenuity and inventiveness that they required. Technologies become repurposed through acts of repair, reuse, and use in new contexts. However, they also take on new life in our memories of them and the stories we tell of their significance. As we care for, tend to, and retell these technology stories, they become part of the narratives about nations and families and part of how we come to understand them.

In 1982, Chile suffered its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression as a result of the neoliberal economic policies put in place by the Pinochet dictatorship. Citroën transferred Don Pedro from Arica to Santiago, the capital city, in 1983. He lost his job two years later and then found work as a taxi driver. In the mid-1990s, Cristian returned to Arica and took a photo of his childhood home. The house still had the fence made of Yagán bumpers.