You were one of the first people to work at the artistic lab SymbioticA at the University of Western Australia and are still based there. Your artistic practice is one of constant collaboration with scientists as well as engineers, musicians, and other artists. How does this interdisciplinary collaboration, alongside working primarily in a lab, alter artistic practice?

Guy Ben-Ary: I’m not sure if “alter” is the right term. I would say inform. SymbioticA is a very enriching environment. Artists and resident researchers from multiple disciplines, scientists, clinicians, and bio-medical engineers are all located in close proximity. I’m constantly “bombarded” with new ideas and techniques and made aware of various research projects. After fifteen years of being there, I’m still learning a lot every single day. The idea of In-potentia started in the lab when I saw a PhD student culturing foreskin cells; and the idea for cellF was born during a lecture I attended, which was given by a stem cell biologist as part of the weekly seminar series of the school. The main benefit is that there is (almost) always someone “that knows” and can direct, assist, or provide useful information.

When your medium is a cell culture in a lab, how is the result defined as art, as opposed to pure scientific research?

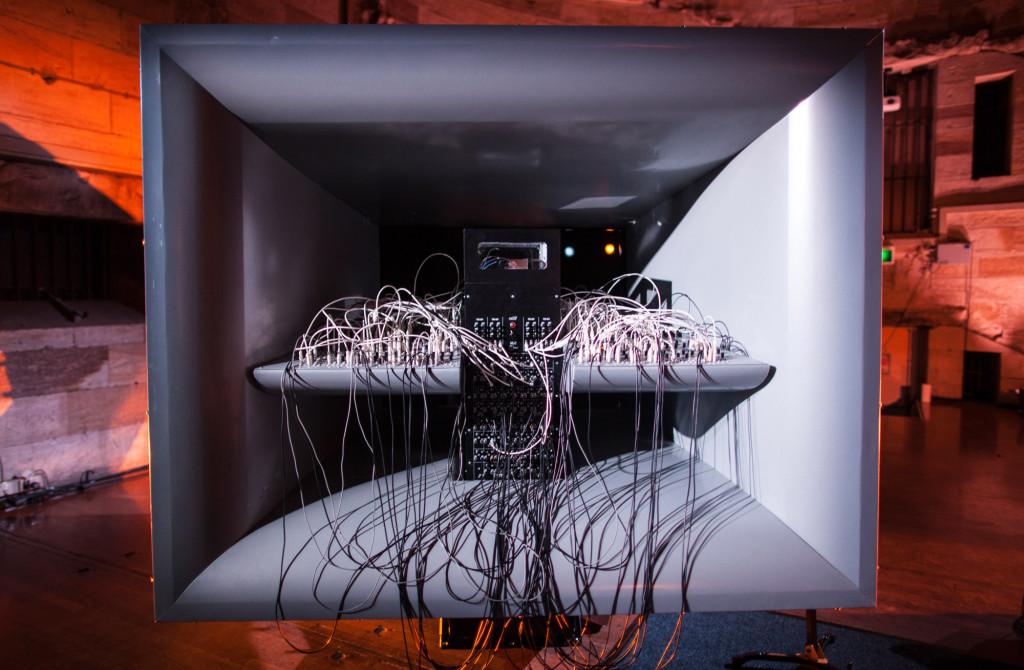

As to cell cultures as art objects, I think this is one of the biggest challenges for so-called “Bio-artists.” Once I figure out the protocols in the lab and thoroughly understand the material I’m working with I ask myself questions related to visual or aesthetic language. In past years I developed various environments/technologies that allowed me to take the living cultures into the gallery. A good example is cellF as an object that not only has a very particular aesthetics and functions as a musical instrument, but is also a fully functioning biological lab that consists of a high-precision tissue-culture incubator and a Class 1 sterile hood, which allows us to keep the neural networks alive in field conditions.

And conversely how do your scientific collaborators feel about devoting resources to a project whose results may not fit into traditional modes of scientific research?

Scientists collect data, but we bring the cultures into galleries and ask questions to generate a cultural debate. It’s totally different. I think the scientists that work with us are as aware of the importance of the cultural research as they are of the scientific one, otherwise they wouldn’t be working with us.

The modern era has stressed the individual over the collective. In cultural production that has led to the myth of the artist as genius, positing the act of artistic creation as uniquely individual. Yet your work, and a lot of new art connected with science and technology, is very much about complex collaboration across fields. Have we reached a paradigm change in what it means to create an artwork in the twenty-first century?

I wouldn’t go as far as a “change of paradigm.” There are still quite a lot of art forms that don’t require collaborations. However, when it comes to projects that involve technology and definitely in my area of research of art, biology, and robotics, collaborative work is very common. The reason for this is the complexity of the projects and the wide range of skill sets that is needed for the development of the work. cellF is my self-portrait and in its early days I thought it would be appropriate to develop it by myself. But that was very naïve of me. Its final outcome involved the following areas of research/production: tissue culture, tissue engineering, neuroscience, cell biology, stem cell technologies, molecular biology, electrophysiology, microscopy, electrical engineering, material engineering, engineering, design, sound, music technology, and more … I could never have done it without my collaborators. They all joined the project as equals despite it being my self-portrait.

You initiated cellF, which is run from a neurons culture containing your DNA. Yet this colony is fully autonomous. Its reactions to input from various musicians demonstrate agency on a cellular level. The culture (of approximately 100,000 neurons) is still one-millionth the size of the human brain, without the complex structure of the latter. We can surmise that it has no “consciousness,” as we know it. But as cellF acts and reacts to the human musicians can we talk about a “neuronal subjectivity” here?

That’s a very interesting question … and very hard to answer. The short answer is that I don’t know. I agree that there is no point in talking about consciousness or intelligence. These cultures are not complex enough. But after experiencing cellF live I have a feeling that maybe we can talk about simple forms of emergence. I think that these neural cultures are active and responsive—but even more interesting is that they show vitality, which is what directs them to do what they do. These neural networks are very simple (made up of only 100,000 neurons and growing in 2D). However, I use living neurons deliberately, as a way to force the viewer to consider future possibilities that neural-engineering and stem cell technologies present, and to begin to assess and critique technologies not commonly known outside the scientific community. However simple or symbolic these brains may be, they do produce quantities of data, and they do respond to stimulation, and they are subject to a lifespan.

cellF has already taken part in seven concerts and at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt performs its European premiere with Schneider TM and then Stine Janvin. What has most surprised you about the ability of neuronal cultures to interact with and create music with human musicians?

Every performance is different and all the performances we have given have been interesting in a different way. But when the neurons respond to the human musicians I get excited. I’m very much interested in human/nonhuman communication. It is when there is a clear sense of communication between human musicians and the neurons that my mind is blown. And this has happened in most performances up till now. I hope we will experience a bit more of that. These neural networks represent our fears and hopes as we enter an unknown future. They illustrate, in a highly visceral manner, popular ideas around disembodied consciousness and intelligence. However, although the neural entities I create might instill a sense that we are close to actualizing the manufacture of intelligence or consciousness, in reality, the existence of these creatures is intended to be absurdly vicarious.